ERCP

ERCP is a procedure that uses an endoscope and X-rays to look at the bile duct and the pancreatic duct. ERCP can also be used to remove gallstones or take small samples of tissue for analysis (a biopsy).

What is an ERCP?

ERCP stands for 'endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography'. ERCP is a very useful procedure, as it can be used both to diagnose and to treat various conditions, such as gallstones, acute pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas that develops quickly over a few days) and chronic pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas that is more persistent).

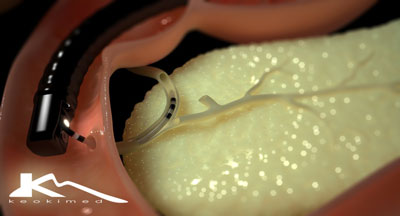

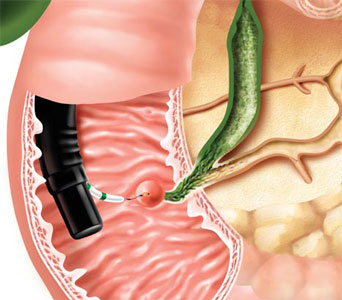

An endoscope is a thin, flexible, telescope. It is passed through the mouth, into the gullet (oesophagus) and down towards the stomach and the first part of the gut after the stomach (the duodenum). The endoscope contains fibre-optic channels which allow light to shine down so the doctor can see inside.

Cholangiopancreatography means X-ray pictures of the bile duct and pancreatic duct. These ducts do not show up very well on ordinary X-ray pictures. However, if a dye that blocks X-rays is injected into these ducts then X-ray pictures will show up these ducts clearly. Some dye is injected through the papilla back up into the bile and pancreatic ducts (a 'retrograde' injection). This is done via a plastic tube in a side channel of the endoscope. X-ray pictures are then taken.

An endoscope is a thin, flexible, telescope. It is passed through the mouth, into the gullet (oesophagus) and down towards the stomach and the first part of the gut after the stomach (the duodenum). The endoscope contains fibre-optic channels which allow light to shine down so the doctor can see inside.

Cholangiopancreatography means X-ray pictures of the bile duct and pancreatic duct. These ducts do not show up very well on ordinary X-ray pictures. However, if a dye that blocks X-rays is injected into these ducts then X-ray pictures will show up these ducts clearly. Some dye is injected through the papilla back up into the bile and pancreatic ducts (a 'retrograde' injection). This is done via a plastic tube in a side channel of the endoscope. X-ray pictures are then taken.

The bile ducts and nearby structures

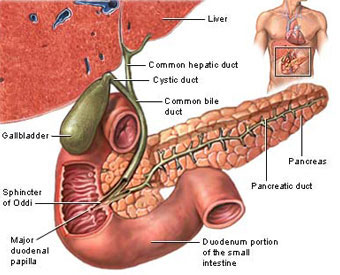

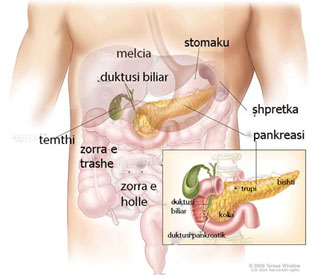

Bile is made in the liver. The liver is in the upper right part of the tummy (abdomen). Bile passes from liver cells into tiny tubes called bile ducts. These join together (like the branches of a tree) to form the common bile duct. Bile constantly drips down the common bile duct,and through an opening called the papilla (see diagram, below) into the first part of the gut after the stomach (the duodenum).

The gallbladder lies under the liver on the right side of the upper abdomen. It is like a pouch which comes off the common bile duct. It is a 'reservoir' which stores bile between meals. The gallbladder squeezes (contracts) when you eat. This empties the stored bile back into the common bile duct. The bile passes along the remainder of the common bile duct into the duodenum. Bile helps to digest food, particularly fatty foods. The pancreas is a large gland that makes chemicals (enzymes). These flow down the pancreatic ducts, into the main pancreatic duct,and through the papilla into the duodenum. The pancreatic enzymes are vital in order to digest food. (The pancreas also makes some hormones such as insulin.)

What happens during an ERCP?

What happens during an ERCP?

The doctor may numb the back of your throat by spraying on some local anaesthetic, or may give you a lozenge to suck. You will usually be given a sedative by an injection into a vein in the back of your hand or arm. The sedative makes you drowsy and relaxed but it does not 'put you to sleep'. It is not a general anaesthetic.

You lie on your side on a couch. The doctor will ask you to swallow the first section of the endoscope. Modern endoscopes are quite thin (thinner than an index finger) and quite easy to swallow. The doctor then gently pushes it down your oesophagus into your stomach and duodenum.

The doctor looks down the endoscope via an eyepiece or on a TV monitor which is connected to the endoscope. Air is passed down a channel in the endoscope into the stomach and duodenum to make the lining easier to see. This may make you feel 'full' and want to belch.

The endoscope also has a 'side channel' down which various tubes or instruments can pass. These can be manipulated by the doctor who can do various things. For example:

- Inject a dye into the bile and pancreatic ducts. X-ray pictures taken immediately after the injection of dye show up the detail of the ducts. This may show narrowing (stricture), stuck gallstones, tumours pressing on the ducts, etc.

- Take a small sample (biopsy) from the lining of the duodenum, stomach, or pancreatic or bile duct near to the papilla. The biopsy sample can be looked at under the microscope to check for abnormal tissue and cells.

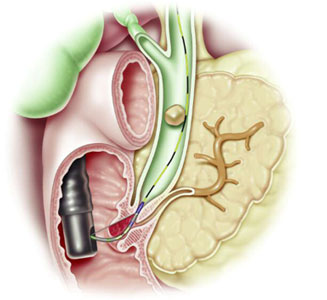

- If the X-rays show a gallstone stuck in the duct, the doctor can widen the opening of the papilla to let the stone out into the duodenum. A stone can be grabbed by a 'basket' or left to be passed out with the stools (faeces).

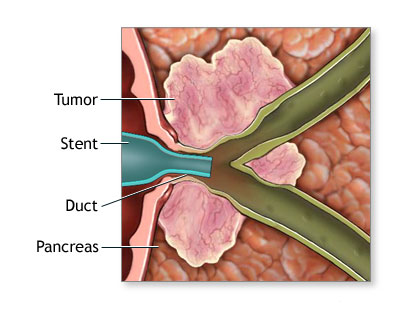

- If the X-rays show a narrowing or blockage in the bile duct, the doctor can put a stent inside to open it wide. A stent is a small wire-mesh or plastic tube. This then allows bile to drain into the duodenum in the normal way. You will not be aware of a stent, which can remain permanently in place.

The endoscope is gently pulled out when the procedure is finished. An ERCP can take anything from 30 minutes to over an hour, depending on what is done.

What preparation do i need to do?

You should get instructions from the hospital department before an ERCP. The sort of instructions given include:

- You should not eat for several hours before the procedure. (Small sips of water may be allowed up to two hours before the procedure.)

- Advice about medication which you may need to stop before the procedure.

Medication

Please check with your doctor or testing center for instructions if you are taking any of the following medications:

- Over-the-counter medication

- Diabetes medication (insulin, Glucophage, or others)

- Aspirin

- Coumadin

- Heart medication

- Antacids

What can I expect after an ERCP?

If the procedure was done just to obtain X-ray pictures then most people are ready to go home after resting for a few hours. You should not drive, operate machinery or drink alcohol for 24 hours after having the sedative. If you go home on the same day as the procedure you will need somebody to accompany you home and to stay with you for 24 hours until the effects of the sedative have fully worn off.

Most people are able to resume normal activities after 24 hours. Because of the effect of the sedative, most people remember very little about the procedure. You may require a short hospital stay if you had a procedure such as removing a gallstone or inserting a small wire-mesh or plastic tube (a stent).

Are there any side-effects or complications from having an ERCP?

Most ERCPs are done without any problems. Some people have a mild sore throat for a day or so afterwards. You may feel tired or sleepy for several hours, caused by the sedative. Uncommon complications include the following:

- There is a slightly increased risk of developing a chest infection following an ERCP.

- Occasionally, the endoscope causes some damage to the gut, bile duct or pancreatic duct. This may cause bleeding, infection and, rarely, perforation. If any of the following occur within 48 hours after an ERCP, consult a doctor immediately:

- Tummy (abdominal) pain - in particular, if it becomes gradually worse and is different or more intense to any 'usual' indigestion pains or heartburn that you may have.

- Raised temperature (fever).

- Difficulty breathing.

- Bringing up (vomiting) blood.

- Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) sometimes occurs after ERCP. This can be serious in some cases.

The risk of complications is higher if you are already in poor general health. The benefit from this procedure needs to be weighed up against the small risk of complications.

Let your doctor know if you think you could be pregnant. It may still be possible to perform ERCP if you are pregnant, providing certain precautions are taken. Alternatively, it may be possible to delay it or use another type of procedure.

Indications for ERCP:

Removing stones

Removing stones

Endoscopic clearance of stones from the bile duct may be performed before or after elective cholecystectomy, although laparoscopic bile duct exploration is also acceptable for clearing bile duct stones. The added benefit of endo- scopic sphincterotomy to augment bile drainage for prevention of stone recurrence has not been compared with the laparoscopic approach, which is a relatively recent intervention.

Treating bile duct leaks

Bile duct leaks are quite amenable to endo-scopic biliary sphincterotomy and stent place- ment. The most common signs and symptoms of a leak are drainage of bile via an abdominal drain and collection of bile in the peritoneum, resulting in pain and fever. Success rates for correcting bile duct leaks via ERCP are more than Liver transplant patients are candidates for ERCP with stent placement when a leak occurs early after transplantation, or later with removal of a biliary T-tube.

Correcting strictures

Injury to the common bile duct, common hepatic duct, or an accessory right bile duct that results in a stricture may occur as a result of cholecystectomy (both open and laparo- scopic). Generally, stricture presents as jaundice or as a rise in levels of alkaline phos- phatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.

Endoscopic correction of strictures is usually done via dilation—with tapered rigid dilators or high-pressure balloon catheters—and then placement of multiple stents. This approach is effective and can make surgical intervention unnecessary in many cases. The short-term success rate in anastomotic strictures following liver transplantation approaches 80% to 90%.

Patients with biliary strictures are scheduled for exchange of plastic stents and progressive biliary dilations every 1 to 2 months until the stricture resolves.

ERCP IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PANCREATIC AND BILIARY CANCER

ERCP allows access to obstructed bile andpancreatic ducts for collecting tissue samples and placement of stents to temporarily relieve the obstruction.

Diagnostic procedures

ERCP allows access to obstructed bile andpancreatic ducts for collecting tissue samples and placement of stents to temporarily relieve the obstruction.

Diagnostic procedures

The sensitivity of routine brush cytologic study to yield a diagnosis of cancer for malignant strictures is generally low (30%–50%) and may be improved when combined with other techniques such as intraductal biopsy and fine-needle aspiration.

In pancreatic cancer, the malignancy may be adjacent to the bile duct, which results in compression without invasion of malignant cells into the region being sampled. In cholangiocarcinoma, the yield is likely to be poor due to the low cellularity and the highly fibrotic nature of this tumor. The sensitivity of fine-needle aspiration guided by endoscopic ultrasonography is far superior to that of ERCP with brush cytologic or biopsy sampling and is safer.

Stent placement

In patients with unresectable pancreatic and bile duct tumors, endoscopic placement of a bile duct stent is the treatment of choice for palliation of malignant distal bile duct strictures. Proper staging and planning before the procedure may require a multidisciplinary approach, with expertise in radiology and surgery to determine resectability.

The value of endoscopic stent placement in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenec-tomy remains controversial, with some speculating that contamination of the obstructed biliary tree results in a higher postoperative infection rate.

Metal stent vs plastic stent

The decision to place a metal vs a plastic biliary stent arises frequently in the care of patients with malignant obstructions. A randomized trial by Prat et al compared metal stents, plastic stents changed every 3 months, and plastic stents changed only when stent dysfunction was clinically evident. The study found relief of jaundice to be comparable among the three groups. Complication-free survival was longer in those with metal stents and in those with plastic stents that were exchanged every 3 months. Cost analysis showed an advantage to metal stents in patients surviving longer than 6 months, and to plastic stents exchanged every 3 months in those surviving less than 6 months.

Occlusion of plastic and metal stents causes recurrent jaundice, pruritus, and cholangitis. Unfortunately, the only option for metal stent occlusion is to place another stent (plas-tic or metal) within the failed metal stent, because it cannot be removed once the patient’s normal or neoplastic tissue has grown into the fine wire braids. Partial coverings on metal stents did not seem to improve the overall patency rate.Metal stents with a complete covering are expected in the future in the hope of making a large-diameter stent that can be removed.

Biliary obstruction due to hilar tumor.

Endoscopic drainage to relieve biliary obstruction due to a hilar tumor is a particular challenge, whether via ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic access. Whether the best stent material is plastic or metal is still a hotly debated issue. Also, contrast injected during ERCP often enters both lobes of the liver, and leaving undrained contrast material in any segment of the liver is believed to increase the risk of cholangitis.

Unilateral or bilateral stent placement?

The design of uncovered metal stents may afford advantages over plastic stents because it allows drainage of multiple segments through the numerous interstices between the metal wires. MRCP and CT are routinely used to guide percutaneous stent placement, but in one study, some investigators used cross-sectional imaging to guide placement of a unilateral metal stent at the first ERCP procedure in patients who were deemed poor candidates for surgery based on the location of the tumor.

The concern about draining all contrast seemed to be unfounded, as routine antibiotic therapy prevented any episodes of ERCP- induced cholangitis.

Although this was a single-center study, the authors made a convincing argument for use of a unilateral metal stent even in the most complicated cases of hilar cholangiocar- cinoma. In a similar patient population, the authors guided their catheter into the intra- hepatic ducts via the portion of the biliary tree that was most accessible using a guide wire from below the tumor.

The early com- plication rates were low, and jaundice resolved completely in 86% of patients. The overall success rate and low complication rate in these patients suggest that stent placement into both the right and left lobes is not necessary. Previously, retrospective data suggested bilateral placement of plastic stents was associated with a better rate of survival and fewer procedural complications.

However, a ran-domized trial of bilateral vs unilateral stent placement failed to show any advantage to bilateral stent placement.

Percutaneous stent placement

Patients whose symptoms are not adequately relieved by ERCP stents may benefit from the percutaneous approach, since these catheters have multiple side holes that allow flow of bile into the lumen from multiple levels. The risks of the percutaneous approach include peri- tonitis and pain at the insertion site, while the advantages include ease of access to the stent in times of malfunction to assess patency and stent exchange without the need for endo- scopic intervention.

MISCELLANEOUS INDICATIONS FOR ERCP

ERCP is also used in selective cases of pancreatic pseudocyst drainage, pancreatic duct leaks due to trauma or pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis with stone extraction or stricture dilation, and assessment of the biliary and pancreatic orifices during endoscopic removal of adenomas of the duodenum involving the ampulla (ampullectomy).

ERCP is occasionally used for diagnostic purposes when MRCP and other imaging studies are inconclusive or when there is a concern that they would be unreliable. Examples include suspected cases of primary sclerosing cholangitis early in the disease, when the changes in duct morphology are subtle, or in a patient with a nondilated bile duct and clini cal signs and symptoms highly suggestive of a gallstone or biliary sludge (microlithiasis).