Esophageal varices

What are Esophageal varices?

What are Esophageal varices?

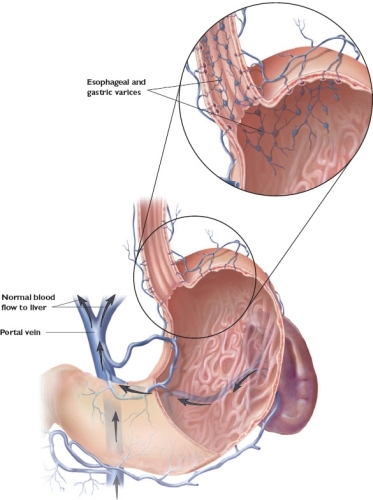

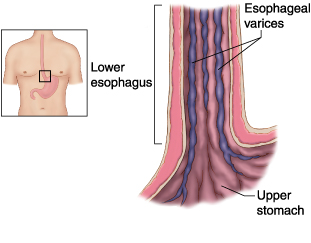

Esophageal varices are abnormal, enlarged veins in the lower part of the esophagus — the tube that connects the throat and stomach. Esophageal varices occur most often in people with serious liver diseases.

Esophageal varices develop when normal blood flow to your liver is slowed.

The blood then backs up into nearby smaller blood vessels, such as those in your esophagus, causing the vessels to swell. Sometimes, esophageal varices can rupture, causing life-threatening bleeding. The size of the varices and their tendency to bleed are directly related to the portal pressure, which is usually directly related to the severity of underlying liver disease

Symptoms

• Vomiting blood Haiatiesis,

• Black, tarry or bloody stools melaena.

• Shock, in severe cases

• Abdominal pain.

• Features of liver disease and specific underlying condition.

• Dysphagia/odynophagia (pain on swallowing; uncommon).

• Confusion secondary to encephalopathy (even coma).

• Pale.

• Peripherally shut down.

• Pallor.

• Hypotension and tachycardia (ie shock).

• Reduced urine output.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any signs or symptoms that worry you. If you've been diagnosed with liver disease, ask your doctor about your risk of esophageal varices and how you may reduce your risk of these complications. Ask your doctor whether you should undergo an endoscopy procedure to check for esophageal varices.

If you've been diagnosed with esophageal varices, your doctor may instruct you to be vigilant for signs of bleeding.

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any signs or symptoms that worry you. If you've been diagnosed with liver disease, ask your doctor about your risk of esophageal varices and how you may reduce your risk of these complications. Ask your doctor whether you should undergo an endoscopy procedure to check for esophageal varices.

If you've been diagnosed with esophageal varices, your doctor may instruct you to be vigilant for signs of bleeding.

Causes:

The enlarged veins of esophageal varices form when blood flow to your liver is slowed. Often the flow of blood is slowed by scar tissue in the liver caused by liver disease. When the blood to your liver is slowed, it begins to back up, leading to increased pressure within a major vein (portal vein) that carries blood to your liver. This pressure forces the blood into the nearby smaller veins, such as those in your esophagus. These fragile, thin-walled veins begin to balloon with the added blood. Sometimes the veins can rupture and bleed.

Liver diseases and other causes of esophageal varices

Esophageal varices are most often a complication of cirrhosis — irreversible scarring of the liver. Other diseases and conditions also can cause esophageal varices.

Causes can include:

• Severe liver scarring (cirrhosis). A number of liver diseases can result in cirrhosis, such as hepatitis infection, alcoholic liver disease and a bile duct disorder called primary biliary cirrhosis.

• Blood clot (thrombosis). A blood clot in the portal vein or in a vein that feeds into the portal vein called the splenic vein can cause esophageal varices.

• A parasitic infection. Schistosomiasis is a parasitic infection found in parts of Africa, South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The parasite can damage the liver, as well as the lungs, intestine and bladder.

• A syndrome that causes blood to back up in your liver. Budd-Chiari syndrome is a rare condition that causes blood clots that can block the veins that carry blood out of your liver.

Risk factors

Although many people with advanced liver disease develop esophageal varices, most won't experience bleeding.

Varices are more likely to bleed if you have:

• High portal vein pressure. The risk of bleeding increases with the amount of pressure in the portal vein.

• Large varices. The larger the varices, the more likely they are to bleed.

• Red marks on the varices. When viewed through an endoscope — a lighted tube that's passed down your throat — some varices show long, red streaks or red spots. These marks indicate a high risk of bleeding.

• Severe cirrhosis or liver failure. Most often, the more severe your liver disease, the more likely varices are to bleed.

• Continued alcohol use. If your liver disease is alcohol related, your risk of variceal bleeding is far greater if you continue to drink than if you stop.

Complications

• Bleeding

The most serious complication of esophageal varices is bleeding. Once you have had a bleeding episode, your risk of another is greatly increased. In some cases, bleeding can cause the loss of so much blood volume that you go into shock. This can lead to death.

Tests and diagnosis

If you have cirrhosis or another serious liver disease, your doctor may screen you for esophageal varices. How often you'll undergo screening tests depends on your condition. Tests used to diagnose esophageal varices include:

Endoscopy is the criterion standard for evaluating esophageal varices and assessing the bleeding risk. This procedure is performed by a surgeon or a gastroenterologist with the patient under light sedation. The procedure involves using a flexible endoscope inserted into the patient's mouth and through the esophagus to inspect the mucosal surface.

When esophageal varices are discovered, they are graded according to their size, as follows:

• Grade 1 – Small, straight esophageal varices

• Grade 2 – Enlarged, tortuous esophageal varices occupying less than one third of the lumen

• Grade 3 – Large, coil-shaped esophageal varices occupying more than one third of the lumen

Imaging tests.

Although endoscopy is the criterion standard in diagnosing and grading esophageal varices, the anatomy outside of the esophageal mucosa cannot be evaluated with this technique.Today, more sophisticated imaging with computed tomography (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) plays an important role in the evaluation of portal hypertension and esophageal varices.

Treatments and drugs

The primary aim in treating esophageal varices is to prevent bleeding. Bleeding esophageal varices are life-threatening. If bleeding occurs, treatments are available to try to stop the bleeding.

Treatments to prevent bleeding

Treatments to lower blood pressure in the portal vein may reduce the risk of bleeding esophageal varices. Treatments may include:

• Medications to slow flow of blood in the portal vein. A type of blood pressure drug called a beta blocker may help reduce blood pressure in your portal vein, reducing the likelihood of bleeding. These medications include propranolol (Inderal, Innopran) and nadolol.

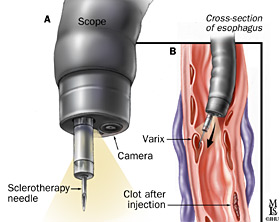

• Using a scope to access your esophagus and treat varices. If your esophageal varices appear to have a very high risk of bleeding, your doctor may recommend some of the same treatments that are used to stop active bleeding. Treatments may involve using an endoscope to see inside your esophagus and inject a medication or tie off veins with an elastic band.

Treatments to stop bleeding

Bleeding varices are life-threatening, and immediate treatment is essential. Treatments used to stop bleeding include:

• Using elastic bands to tie off bleeding veins. During variceal ligation, your doctor uses an endoscope to snare the varices and wrap thi with an elastic band, which essentially "strangles" the veins so they can't bleed. Variceal ligation carries a small risk of complications, such as scarring of the esophagus.

• Injecting a solution into bleeding veins. In a procedure called endoscopic injection therapy, the bleeding varices are injected with a solution that shrinks thi. Complications can include perforation of the esophagus and scarring of the esophagus that can lead to trouble swallowing (dysphagia).

• Medications to slow blood flow into the portal vein. Medications can slow the flow of blood from the internal organs to the portal vein, reducing the pressure in the vein. A drug called octreotide (Sandostatin) is often used in combination with endoscopic therapy to treat bleeding from esophageal varices. The drug is usually continued for five days after a bleeding episode.

• Diverting blood flow away from the portal vein. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystiic shunt (TIPS) is a small tube that is placed between the portal vein and the hepatic vein, which carries blood from your liver back to your heart. By providing an additional path for blood, the shunt often can control bleeding from esophageal varices. But TIPS can cause a number of serious complications, including liver failure and mental confusion, which may develop when toxins that would normally be filtered by the liver are passed through the shunt directly into the bloodstream. TIPS is mainly used when all other treatments have failed or as a tiporary measure in people awaiting a liver transplant.

• Replacing the diseased liver with a healthy one. Liver transplant is an option for people with severe liver disease or those who experience recurrent bleeding of esophageal varices. Although liver transplantation is often successful, the number of people awaiting transplants far outnumbers the available organs.

Prevention

If you've been diagnosed with liver disease, you may worry about your risk of complications if your liver disease worsens. Ask your doctor about strategies to avoid liver disease complications. It may help to take steps to keep your liver as healthy as possible, such as:

• Don't drink alcohol. People with liver disease are often advised to stop drinking alcohol, since alcohol is processed by the liver. Drinking alcohol may stress an already vulnerable liver.

• Eat a healthy diet. Choose a plant-based diet that's full of fruits and vegetables. Select whole grains and lean sources of protein. Reduce the amount of fatty and fried foods you eat.

• Maintain a healthy weight. An excess amount of body fat can damage your liver. Lose weight if you are obese or overweight.

• Reduce your risk of hepatitis. Sharing needles and having unprotected sex can increase your risk of hepatitis B and C.

Protect yourself by abstaining from sex or using a condom if you choose to have sex. Ask your doctor whether you should be vaccinated for hepatitis B.